More than 1,400 miles from the Appalachian Trail’s beginning at Springer Mountain, Georgia, there’s a short loop off the main trail that leads to a small, pristine lake on the eastern edge of New York, just a few miles from the Connecticut border. Getting to the loop requires a moderate, but occasionally tricky, 1.1-mile hike from the nearest parking lot, but the payoff is worth it: a secluded, Edenic lake that appears almost untouched by humans. There’s an earthen dam and some fence-work on the southern shore, but it’s easy to work your way around to places completely unspoiled. Maples and oaks canopy out over clear water. The air is fresh. Around you, boulders of banded gneiss and schist rise out of the dirt, remnants of a time nearly half a billion years ago when these woods formed the eastern shore of the Iapetus Ocean.

For northbound through-hikers on the Appalachian Trail, it can be a welcome respite. Rahawa Haile, who hiked the trail in 2016, told me that the lake represents a parting embrace from New York’s deceptively difficult 90 miles of trail and a welcome sign that Connecticut beckons. For locals, it’s a hidden gem: free of easy vehicle access and thus free of hordes of tourists, even during the summer months. Hiker Jeff Walden has called it “easily the most beautiful lake on the entire trail.”

Everything about this place is placid and calm, except its name: Nuclear Lake.

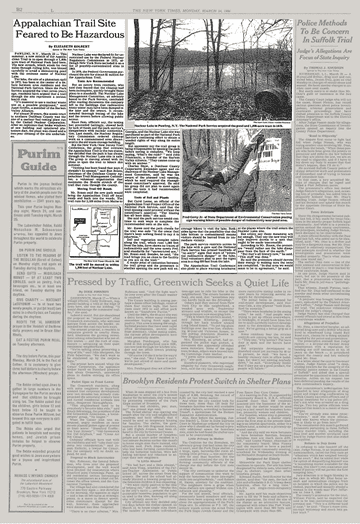

(Photo: The New York Times)

The lake’s name came from Nuclear Development Associates (later United Nuclear Corporation), which bought this wilderness north of the town of Pawling, New York, in 1958. Then one of only a handful of private companies licensed to handle plutonium, the company ran a small-scale research and development lab. It had chosen the site, the New York Times reported in 1958, “because it was the largest convenient and available tract that was not crossed by public roads and could be adequately guarded for secret experiments.” For the next 14 years, UNC’s plant was used primarily to test and produce reactor fuel rods—tubes filled with pellets of radioactive material that are used to power nuclear reactors. But in 1972, a glovebox (one of those sealed chambers with built-in gloves designed to allow employees to handle dangerous materials) triggered an explosion that blew out the plutonium laboratory’s north-facing windows, sending clouds of plutonium dust through the room and out into the environment. There were no reported fatalities, but the explosion contaminated the building and left radioactive material to soak into the soil. Within a year, UNC had closed down the plant—though director of shareholder relations, Richard C. Ross, cited not the explosion, but a “commercial decision,” according to the Times, and partner companies sought to retain the plant’s licenses. But, after inspecting the site, the Atomic Energy Commission (now the Nuclear Regulatory Commission) terminated the company’s licenses. Despite remediation work done to eliminate contaminants, the site sat unused until the Department of the Interior bought it and the surrounding area, just over 1,100 acres, on behalf of the National Park Service in 1979.

The government bought the land in an effort to move this portion of the Appalachian Trail off of paved roads and back onto a wilderness path. That meant routing one of the country’s most popular hiking trails past a lake with a difficult past. “Never before has the Federal Government tried to turn land owned by the private nuclear industry to public recreational use,” the Times reported in 1980. Confusion about how safe the land was persisted; in 1974, the surrounding wilderness had been remediated to levels the federal government deemed acceptable for unrestricted use, but the site of the facility was still inacessible. According to an Associated Press story in 1986, hikers who strayed too far from the Appalachian Trail were met with signs that read: “Property of U.S. Government. No Entry Beyond This Point. Potential Radioactive Danger.”

For years, residents fought both the NPS and the nuclear industry, warning of dire consequences should the lake be opened to the public. “It’s immoral to use a nuclear waste site as a possible playground,” one activist told the Times in 1986. But by 1994, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission had released the site for unrestricted use, and, since then, its popularity as a recreation destination has grown steadily.

On an afternoon in August of 2018, much of that history seemed very far away. My wife and I brought our dog to the banks of Nuclear Lake and watched a group of men with fishing poles take up position along the western shore. Most of the hikers I encountered on the way up had only the dimmest recollection of the story or of how the lake got its name. Those who knew there had been an explosion were all quick to affirm that it was now safe. There are rumors (unfounded, of course) that the bass in Nuclear Lake are abnormally large—the kind of myth-making designed to portray any lingering radiation effects as positive.

Looking at the dozen or so people enjoying this late summer day, you’d never imagine the battle over this land from the 1980s, when locals fought hard to keep people away from what they believed to be an environmental menace. But we have short memories, and the herd effect is powerful: The more people who come here, the more others assume it’s safe. Even before the site had been released, locals were stealing away to fish here anyway, as though the lake’s natural beauty exerted a magnetic pull.

A local named John, from nearby East Fishkill, said he’d been coming here regularly for the past two years. “They say it’s been cleaned up,” he said. But, looking back at the water, he quickly added, “I don’t know, though, maybe I shouldn’t come here as often as I do.”

America’s nuclear past usually conjures up a short list of infamous sites: Three Mile Island, Hanford, Trinity. Such names evoke fears of long-term health effects, landscapes scarred and uninhabitable, rusted signs warning of dire consequences for trespassers. The nuclear frontier, with its secret government labs and Superfund sites, has left blank spaces on the map, eerie gaps in geography where the public fears to tread. But along that frontier are also far less foreboding places: nondescript industrial buildings and office parks, along with out-of-the-way, natural places like Nuclear Lake.

In 1994, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission removed the Pawling site from its Site Decommissioning Management Plan (those sites requiring “special attention” for excessive contamination levels), citing outside surveys that confirmed the site’s radiation levels as “acceptable to the NRC.” New York’s Cancer Registry doesn’t indicate a particularly high incidence of cancer in the town of Pawling relative to the rest of the state, but local residents have sometimes looked to the accident of nearly 50 years ago to explain their current illnesses, whispering on hiking blogs about suspicions that their cancer diagnoses have something to do with Nuclear Lake. The explosion’s legacy lingers not in a blast crater or irradiated fish, but in a name that stuck—and in rumors that there’s still poison in the air.