Stephanie Allain doesn’t have the same name recognition among American cinephiles as directors like John Singleton or Justin Simien, but she has spent 31 years as the secret force ushering their work—and that of many other black and Latino filmmakers—into movie theaters around the world. As a producer and creative executive, Allain nurtured minority talent at Columbia Pictures in the 1990s, where she pitched Singleton’s Boyz N the Hood script to her bosses and developed Robert Rodriguez’s El Mariachi and Darnell Martin’s I Like It Like That. Since 2003, Allain has worked outside the studio system at her production company, Homegrown Pictures, where she has helped produce some of this decade’s most consequential films and television series by black creators. Hustle and Flow might never have gotten off the ground if Allain hadn’t sold her house and enlisted Singleton to help finance it; Beyond the Lights, Dear White People (the 2014 film and 2017 TV series), and Burning Sands are all Homegrown productions. Between 2012 and 2016, Allain worked to diversify the Los Angeles Film Festival, where, as festival director, she instructed employees to double down on the festival’s mission of representing filmmakers of many experiences. As Allain’s career reminds us, producing movies that truly reflect the American populace requires not only good intentions—it also requires concrete support, at all levels of the entertainment industry.

Books

The Art of Happiness

Over the past decade, studies have linked happiness to a stronger immune system, longer lives, and career success. So how does one attain it? The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for Living (1999), co-authored by the 14th Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso and psychiatrist Howard C. Cutler, offers a multidisciplinary roadmap. The book combines Western medical advances with Buddhist principles to argue that one can train one’s mind toward happiness. Some of its advice is abstract—seekers must cultivate compassion, selflessness, and generosity, the Dalai Lama argues. But skeptics can now consult the growing body of “positive psychology” studies that surged in the 18 years since the book’s release: These days, the art of happiness is also a robust field of scientific study.

Why

“I happened upon this book when I was miserable from a broken heart. It’s an easy way to train your mind to understand how we control our own happiness. This ‘handbook for living’ does more to help erase worry and stay present with a simple idea: Feel empathy for those less fortunate—a solid way to generate gratitude and get out of your own way.”

Man’s Search for Meaning

In the two and a half years Viktor Frankl spent at concentration camps during the Holocaust, nearly everyone close to him died—including his pregnant wife and his mother, father, and brother. Nevertheless, Frankl says, he still had “the last of the human freedoms,” as he wrote in his 1946 memoir of the camps, Man’s Search for Meaning: “To choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” Frankl argues that, in his time at the camps, prisoners who took the initiative to find meaning in their lives—even under their extraordinary circumstances—survived longest. These observations would later inspire Frankl to found logotherapy, a school of psychotherapy positing that the search for a greater purpose in one’s life is the primary motivator of human beings.

Why

“I keep it near my toilet. Just flipping through the pages fills me with awe and gratitude for the existence of a document that proves the strength of getting your mind right. As Frankl articulates how he found mental freedom under the most oppressive situation, it reduces the impact of the daily micro-aggressions I endure as a black woman in America.”

Memoir

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

Published in 1969 to critical acclaim, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings—a memoir of author Maya Angelou’s life from three to 17 years old—has never gone out of print. The book even saw its sales increase 500 percent after Angelou read a poem at Bill Clinton’s 1993 presidential inauguration. The success of Caged Bird was followed by six more autobiographies from Angelou, including Gather Together in My Name (1974) and The Heart of a Woman (1981). Perhaps the book’s greatest triumph, though, was to counteract a nasty American publishing myth: It proved that memoirs from black women can sell well, in defiance of a decades-old stereotype that such books weren’t marketable to the reading masses.

Why

“I was probably 10 when I first read this book. The way Angelou spins her authentic story, filled with horror and liberation, gave me courage as a young black girl to know that I could triumph over anything. From getting her first period to surviving rape, her autobiography is a magnificent testament to the human spirit.”

Novel

The Scarlet Letter

Before Knocked Up and Juno, there was The Scarlet Letter, which provided one of American culture’s earliest icons of defiant mothers with children born out of wedlock, and the social hang-ups that make their lives so difficult. In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1850 novel, set in the 17th-century Massachusetts Bay Colony, protagonist Hester Prynne is publicly shamed after bearing a child while her husband is away at sea. Though pressured to identify the father by Boston society, she never utters his name, and endeavors to flee with him and her young daughter to Europe for their collective safety while balancing her own battles for custody over her child.

Why

“Hawthorne’s use of story to communicate moral imperatives in expressly stated themes made me want to tell stories. His compassion for Hester Prynne was palpable and her quiet confidence in the face of humiliation and steadfast refusal to out the local preacher struck me as the epitome of feminine strength. Still she persisted.”

Film

Don’t Look Now

Though perhaps most famous for its steamy sex scene, Don’t Look Now resembles a horror film more than it does a romance. After a couple loses their daughter in a drowning accident, John (Donald Sutherland) and Laura (Julie Christie) Baxter travel to Venice, where John has gotten a commission to restore an old cathedral. Though the couple assumes the trip will provide a welcome change of scene, John soon begins experiencing hallucinations of his daughter running around the city—and, after a few, he begins to follow her. Director Nicolas Roeg brings John’s confused state of mind to life with frequent flashbacks and cinematography that frames Venice as an empty maze of waterfront buildings.

Why

“Set in Venice, a 1973 supernatural thriller starring Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie is about a man with the gift of second sight, coping with grief after the drowning of his young daughter. Gothic, sexy, and brimming with unresolved emotion, with one of the best sex scenes ever filmed, it’s all about the importance of believing in your own intuition.”

Musical

Sunday in the Park With George

Many paintings have depicted great plays, but few great plays have sprung from paintings. A notable exception is composer Stephen Sondehim and writer James Lapine’s Sunday in the Park With George, which dramatizes George Seurat’s famous 1884 pointillist painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. With its suggestion that an artist’s existential crisis often precedes the innovation of new styles, Sunday in the Park With George has been considered one of Sondheim’s most personal works. The first production, in 1984, after all, followed a commercial failure for Sondheim, Merrily We Roll Along—but was itself hailed as an innovative work.

Why

“An ode to the artist’s dilemma: Sondheim musicalizes the struggle of balancing the call to create with the importance of nurturing a connected relationship. Harmony. Color. Light. My husband is Grammy winner Stephen Bray, who wrote music and lyrics for The Color Purple. He’s been my guide into the world of musical theater—and I’m completely hooked.”

Television

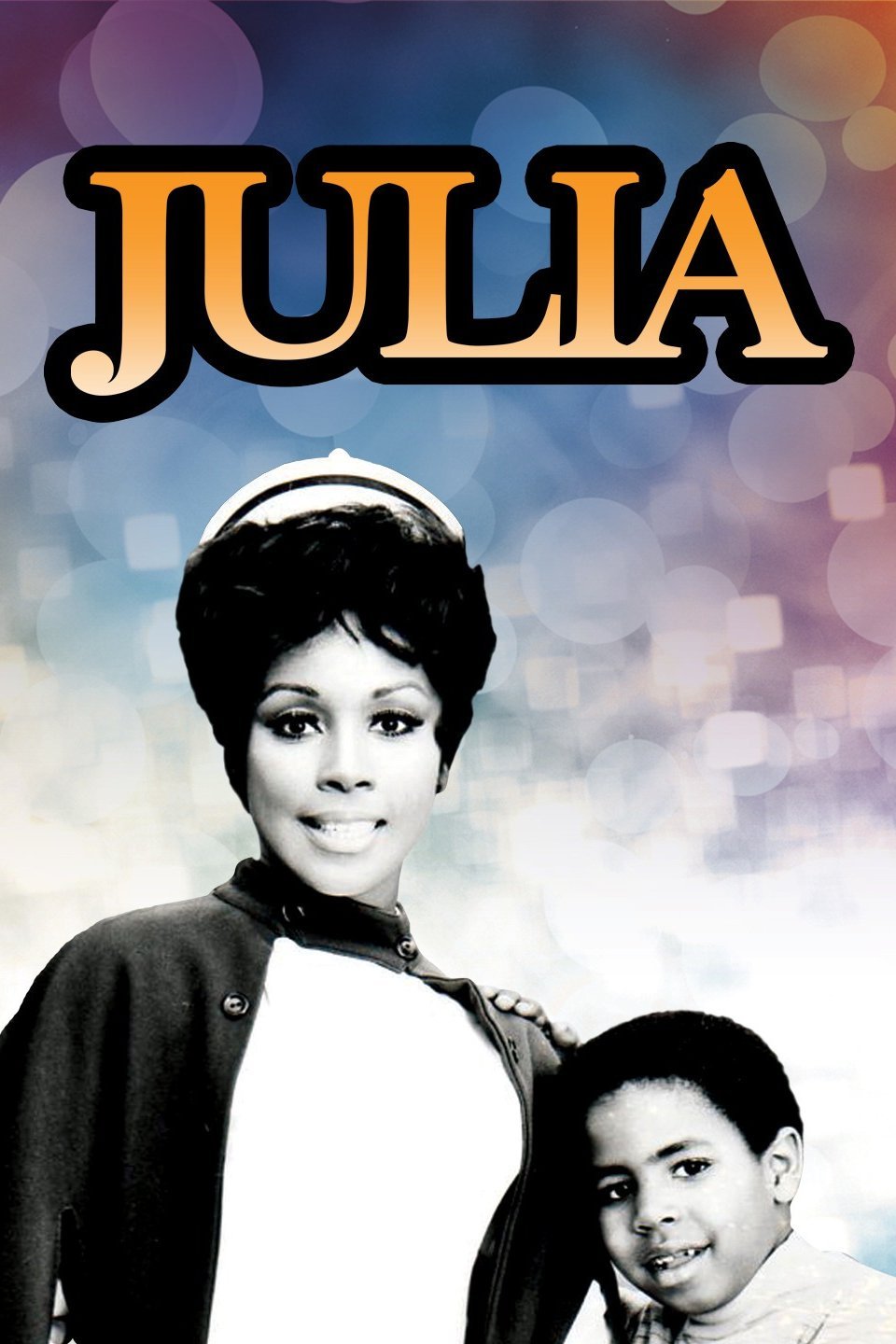

Julia

Before NBC’s half-hour situational comedy Julia premiered in 1968, no black woman had ever starred in a major TV series as anything other than a domestic servant. In sharp contrast, showrunner Hal Kanter’s series cast Diahann Carroll as a middle-class nurse who lived in a well-appointed Los Angeles apartment with a large-screen TV. Though Julia was criticized for rarely tackling racism in its storylines, and for offering no black male role models (Julia was a widow with a son), Kanter argued that the series didn’t aim to document the reality of African-American life in America. Rather, the point of it, he once said, was “that a Negro family is featured, and they’re not choppin’ cotton and they’re not on relief, but they’re part of what some people consider the mainstream of American life.”

Why

“I was hooked on TV shows from the mid- to late-’60s featuring young women—Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, That Girl … but it wasn’t until Julia came on that I recognized the power of inclusive representation. Julia, like my mother, was a black working mom. The fact that someone thought her life was worthy of her own TV show convinced me that my mom’s life mattered. That my life mattered. My passion to support authentic voices must have been seeded then.”

Music

Adagietto, Mahler’s Fifth Symphony

Wedged between two hard-edged movements heavy with Bach-like counterpoint, the fourth movement of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony offers a welcome respite from the darker tone of the overall work. Composed only of strings and a harp, the movement begins simply and mysteriously—with moody strings that ensure that, even in the eye of the symphony’s storm, the tension never fully dissipates—and concludes in a grand, melancholy, romantic melody.

Why

“[I] could listen to this endlessly. The quiet strings that swell with ecstasy embody human emotion. I performed as a dancer to this piece in college and whenever I hear it I am transported back to that theater, to that piece, and to my brief but passionate commitment to dance.”

Album

Hot Buttered Soul

What do Tupac Shakur’s “Me Against the World” and Public Enemy’s “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos” have in common? Besides being hip-hop songs from the late 20th century, both of their beats take a sample from Hot Buttered Soul, a revolutionary 1969 soul album by Isaac Hayes that has influenced the hip-hop and soul genres equally. Produced after his debut album, Presenting Isaac Hayes, bombed commercially, Hayes demanded complete creative control on Hot Buttered Soul. The request paid off: The album hit No. 1 on the R&B and Billboard‘s Top Jazz Albums charts. Today, his rendition of “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” is credited with starting the “love man” genre later popularized by Barry White and Marvin Gaye.

Why

“There are only four tracks on the entire album, including a 12-minute ‘Walk on By’ and an 18-minute ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix.’ To this day, no better lovemaking album. Period. This album cover made bald sexy.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the October 2017 issue of Pacific Standard.