In 2004, Qatar tried to buy their way to the World Cup. This wasn’t the country trying to buy the rights to host the tournament (that would come in 2012). This was the Gulf nation attempting to qualify for the tournament by bringing in a small cadre of talented Brazilian players and giving them Qatari citizenship. These players—Ailton, Dede, and Leandro—were to receive $1 million in exchange for representing Qatar. But then FIFA stepped in and put a stop to it. Soccer’s international governing body ruled that players must have a “clear connection” to a country they want to represent if it is not the country of their birth.

Qatar may have been the most brazen attempt to game the rules on eligibility for national teams, but questions about the eligibility of players for various national teams have only increased since 2004. In order to represent a country other than that in which a player is born, FIFA today requires the player to have a parent or grandparent from another country or have lived in that country for at least five years after the age of 18.

Most cases of dual nationals today do not involve sacks of Qatari cash, but instead are the result of increasing global migration. The United Nations estimates that 232 million people (3.2 percent of the world’s population) are migrants (someone who has crossed an international border), up from 154 million in 1990. The children of these migrants often have dual or multiple citizenship and which country they choose to represent can become a matter of incredibly complex negotiations (see Julian Green, German-American midfielder, who was recently convinced by Jurgen Klinsmann, the legendary German striker, to play for the United States, the country Klinsmann now coaches).

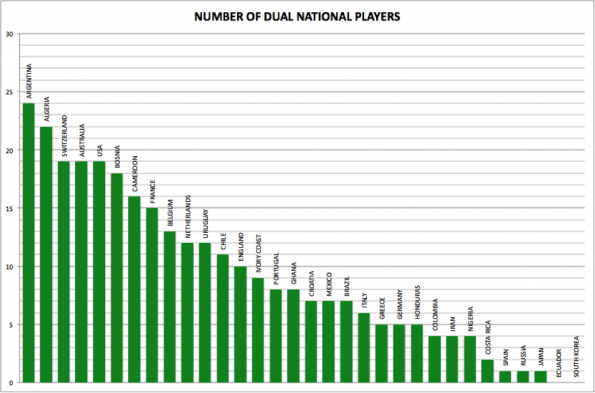

Just how prevalent are dual national players? Using the website TransferMarkt along with other sources, I went through the preliminary rosters for the 2014 World Cup (which have since been cut down to 23) and counted. (See the full data here.)

(Two brief notes on methodology: 1. For brevity, I am using the term “dual national” in spite of the fact that a few players actually have multiple citizenship; 2. While not all of the players I count as dual nationals have dual citizenship at the moment, I counted them as dual nationals if they have either a parent or grandparent from another country, which would enable them to fairly easily obtain a second passport. A good example of this is Maurice Edu, whose parents are Nigerian, but who, as far as I can tell, does not have Nigerian citizenship.)

Of the 958 players named on the initial 30-man rosters (Uruguay chose only to name 28), 30 percent are dual nationals. There is a huge range of the number of dual national players on various teams. Argentina tops the list, with 24. Ecuador and South Korea have none.

It is perhaps not surprising that Argentina has so many dual national players, as the country saw huge waves of migration from Europe (Spain and Italy, in particular) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, many of the descendants of these European migrants are obtaining passports from the countries their ancestors left in order to play for European club teams without counting against quotas on non-E.U. players. The high number of dual national players representing Australia, Brazil, and Uruguay can be explained similarly.

There are occasionally unforeseen consequences to such players getting European passports to advance their club careers, as a few go on to represent the countries of their ancestors. Brazilian-born Thiago Motta (Italy) and Argentine-born Gabriel Paletta (Italy) are two examples from this year’s tournament. (They follow in a long line of so-called oriundi). And some players, having met the five-year residency requirement, represent countries in which they play for club teams (see Brazilian-born Spanish international Diego Costa).

Most dual nationals, though, are simply immigrants, or children of immigrants. The 19 dual nationals who represent Switzerland have dual nationalities as diverse as Bosnia, Kosovo (more than one-sixth of all Kosovars live in Switzerland today), Turkey, Cape Verde, and Ivory Coast. Famously neutral Switzerland does not have the deep colonial legacy that other European countries do, though a referendum narrowly passed in February appears likely to implement limits on the number of immigrants in the country. These colonial legacies shape the make-up of the national teams of countries such as France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, all of which have many players whose families hail from former colonies.

If immigration has proved a source for many of the dual national players we see, so too has emigration. Nearly half of the players on the French team, for example, are dual nationals, but the roster of Algeria, the former French colony, consists of 23 players born in France to Algerian families. Cameroon and Ivory Coast have taken a similar approach to the recruitment of European-born players.

Other countries with significant representation of emigrants on their rosters include the United States, with its strong German-American contingent. Players with an American passport or who will soon be eligible for one were selected for Italy (Giuseppe Rossi), Mexico (Isaac Brizuela and Miguel Ponce), Honduras (Andy Najar and Roger Espinoza), Iran (Steven Beitashour), and Japan (Gotoku Sakai).

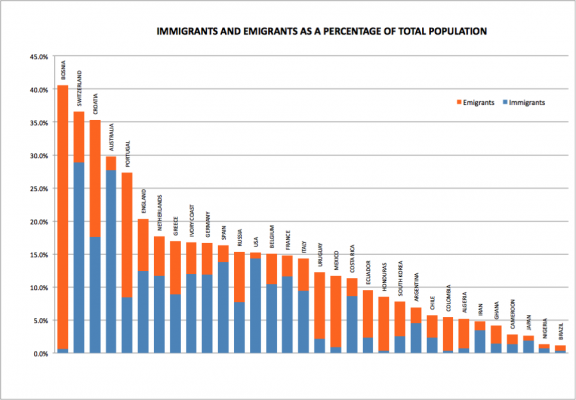

Should we be surprised that there are so many dual national players? One way to judge this is to compare the rates of dual national players to the percentage of both immigrants and emigrants from the countries participating in the World Cup.

Combining the percentage of immigrants and emigrants as a percentage of the total population, we see that some countries have a much greater percentage of people who might be eligible for dual citizenship. We would expect Bosnia, for example, with over 40 percent of its population consisting of immigrants and emigrants, to have many dual national players. Brazil, with only around one percent, should have many fewer.

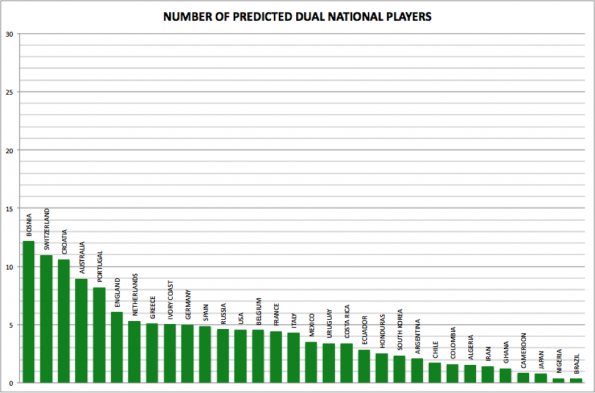

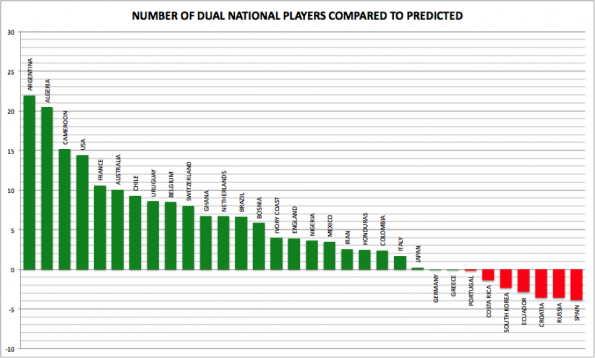

If roster spots should go to dual nationals at the same rates as others, then based on the percentage of immigrants and emigrants, we can predict the number of dual national players that a country should have on its World Cup roster. And this predicted number, for most countries, is lower than the actual number of dual national players.

Why are there more dual national players on the preliminary World Cup rosters than we would expect to see? Leaving aside the pragmatic soccer-specific reasons (i.e. players getting E.U. passports to avoid quotas) and generalizing over some country-specific differences, it seems dual nationals are devoting more energy to sports than others. This may be because many of ethnic and racial minorities in the places where they live and have fewer economic opportunities in general, so instead they hope to find a way out of poverty through sports. Scholars have argued for the importance of this phenomenon—think of it as the Hoop Dreams effect—to explain the over-representation of minorities in the NBA and NFL, and it may be happening in other countries as well. French-Algerian boys in Paris, Swiss-Kosovars in Geneva, and Mexican-Americans in California may all see a similarly limited economic picture and instead hope to make it big through soccer.

What about the countries with fewer dual national players than we would expect? South Korea and Russia have strict immigration policies that make it difficult for outsiders to obtain citizenship, and both countries haven’t harnessed their emigrant populations at all. Spain, Portugal, Germany, and Croatia, it could be argued, have done such a good job with youth development that they have less need to use dual national players.

The future is likely to see the number of dual national players rise. Some countries may try to take advantage of the system. Lawyer Adam Lovatt warns that Qatar may not be done seeking to get around FIFA regulations, and could seek to recruit future Qatari national team players by “lur[ing] footballers to play football in that country for five years from 2017 with the promise of a World Cup tournament appearing on their CV.” More often, though, we will see players with difficult choices to make about which country to represent. In a world of dual and multiple nationalities, soccer is one of the few places in which people have to choose just one.