Here’s the bad news: Bullying in the United State is not declining, and even worse, cyberbullying is increasing. Like all generalizations, that one limps a bit, but the sad fact is that according to the latest research, this time-dishonored practice of bigger and older kids mistreating smaller and younger kids (two more generalizations) has not decreased, and the incidence of cyberbullying (a form of bullying done online) is showing a decided uptick.

The concern resonates in Washington, D.C., where Rep. Linda Sanchez, a California Democrat, last week introduced federal anti-cyberbulling legislation. When she introduced the same bill last May, Sanchez said, “Without a federal law making cyberbullying a crime, cyberbullies are going unpunished.”

But there is also good news: a huge increase in the awareness factor (and the number and quality of anti-bullying programs) thanks to the efforts of schools, parents, communities and students themselves.

One new research effort is the book Bullying Beyond the Schoolyard: Preventing and Responding to Cyberbullying by Justin W. Patchin and Sameer Hinduja, criminologists at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire and Florida Atlantic University, respectively.

Their joint research effort (which led to the book) met with such great interest that they’ve had to take their show on the road, traveling across the country to teach parents and educators how to guard their kids’ online safety. They’ve also set up an online clearinghouse to provide additional information on the subject, which they define as “willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers, cell phones, and other electronic devices.”

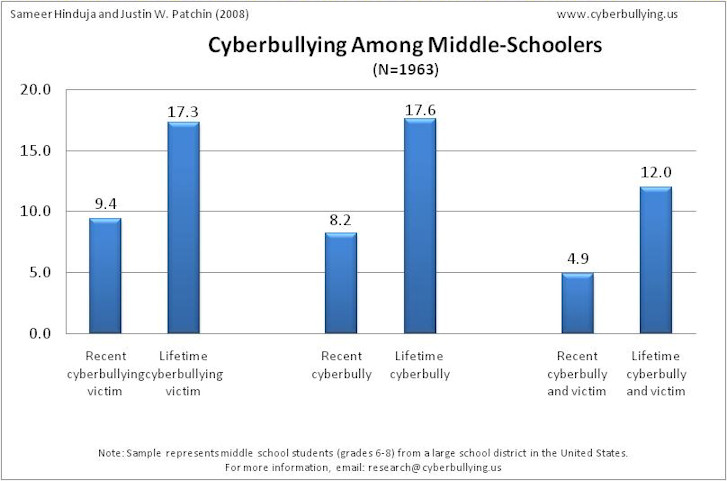

“I would probably agree with the thesis” that bullying has not decreased and cyberbullying has increased, Patchin told Miller-McCune.com, “but it’s more accurate to say that we are finding out about more incidents of bullying and maybe cyberbullying as well. The research we’ve done over the last five or six years has certainly shown an increase in trend in cyberbullying, but it’s also shown that more and more kids are coming forward, so we’re finding out about more of them.”

Hinduja, Patchin’s co-author, said their book “shows the need to recognize that online bullying is a problem that has real ramifications — emotionally, psychologically and even physical ramifications when we’re talking about suicide — and that there are various sorts of real-world things that schools, as well as parents, can do to prevent and respond to this situation.”

And why the increase in cyberbullying? “Because,” he said, “more and more kids are getting access to technology and starting at a younger and younger age. I talk to elementary school kids, and they’re all about Webkinz and Club Penguin. They’re just super-familiar with social networking sites, and they’re definitely interacting with other kids online, which provides the opportunity for harassment and mistreatment and doing harm.”

That said, all is not doom and gloom on either the bullying or the cyberbullying front. According to Tonja Nansel, an investigator with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development‘s Prevention Research Branch, “Some of the recent data I’ve seen is rather encouraging. While it does show that in most English-speaking countries bullying has either stayed the same or increased, in the United States, bullying among boys has decreased.

“But it also shows that cyberbullying has increased. And, unfortunately, you don’t need a lot of cyber-bullying for it to have an effect — one or two events can have waves of repercussions and lasting effects.” As Catherine Hill, senior researcher at the American Association of University Women — who has been studying harassment, including bullying and cyberbullying — put it, “Cyberbullying gives people a longer arm to reach into other peoples’ lives.”

As to whether or not the increase in anti-bullying programs over the last five to 10 years has proven to be effective, Patchin said, “There are increasingly better programs to deal with bullying, yet we still don’t have a good sense of whether or not they’re effective or to what degree they’re effective. As for cyberbullying, we’re studying the problem and getting a clearer picture of what’s going on, but we don’t have a good sense of what would work to stop or prevent it.”

Hill points out that while a majority of the states now have bullying and cyber-bullying laws, there is little research on their effectiveness. And Patchin, whose doctorate is in criminal justice, has reservations about these efforts.

“I’m skeptical about them; I really don’t want to criminalize this behavior. I think there is a role for both the federal and state governments in terms of educating local school districts about what cyber-bullying is and what they can do about it, and providing resources to help them prevent and respond to online aggression. But criminalization doesn’t seem to me to be the best approach.”

Asked to name effective anti-bullying and cyberbullying programs, the experts interviewed for this article most often mentioned the award-winning Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Based on the groundbreaking research of Norwegian psychologist Dan Olweus in the 1970s, today the program he developed in 1982 is administered by Hazelden, the well-known treatment center in Minnesota, and Clemson University.

Sue Thomas, a manager for business development in Hazelden’s publishing division, said “36 states now have laws that require schools to do something about bullying, which is relatively new and a positive step. In addition, there are lots of strong, effective programs around the country that have been proven to work in reducing bullying. A lot of elementary schools that use the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program have seen a 50 percent reduction in bullying within the first year, and within two years on the secondary level.”

As Ryan Blitstein explained in an earlier Miller-McCune.com article, Olweus “begins with the creation of a committee to oversee the anti-bullying campaign and an anonymous student questionnaire assessing the level of bullying in the school. Teachers and administrators are then trained to deal with bullying, and students and parents are taught about the problem. The school establishes anti-bullying rules, and school staff conducts ‘interventions’ with bullies and their victims.”

And it’s not a panacea — it’s pricey for one thing, and since it’s school-based, it only reaches so far.

(Also cited by several sources as a successful program is the Ophelia Project, which was founded 12 years ago in Pennsylvania by veteran teacher Susan Wellman.)

While Thomas, like the other foot soldiers in the anti-bullying wars, is well aware that bullying is an age-old problem, she feels progress has been made and that even more is possible, given greater awareness and effort on the part of all concerned. Nonetheless, she is particularly saddened by the rise in cyberbullying, which can be even more of a problem for its victims because “it happens 24/7. It’s often done anonymously, so kids don’t even know who is bullying them. And if it is going on at home, then home is no longer a safe environment. So that’s a challenge for the kids. One of the challenges for schools is to figure out what legal rights they have to address it.”

“To be honest,” said Hinduja, “I think bullying is always going to be a problem. We’re always going to have people with different perspectives and from different backgrounds, and we’re always going to have peer conflict and harassment. The big-picture goal is to cultivate empathy to make sure that kids are more careful and understand that just because they say it online doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt. So we need to pique their consciences so that they’re constantly thinking about the issue, and that they watch what they say when they’re making these statements.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.