If you laid eyes on Simionie Kunnuk, a small, gentle older man with a fetching gap-toothed smile, you probably wouldn’t think, “Now, there’s a guy who used to have 300 run-ins with the police every year.” However, in 2007, Kunnuk spent his time chugging malt liquor, urinating in public, sleeping wherever, and screaming at passing white people—his personal revenge for Canada’s horrific treatment of him and other indigenous people. More nights than not, these antics landed him in the drunk tank, the hospital, or wherever else the police carted him off to.

Now, Kunnuk’s life is very different. He doesn’t have any casual run-ins with the police, and is an impressive force in his Inuit community in Ottawa, Canada. One of his main missions is to find other addicts in need of treatment by holding traditional Inuit feasts, during which he offers them companionship and counsel. So what’s the secret to his recovery from the consequences of severe alcoholism? Alcohol. The government gives Kunnuk alcohol.

Kunnuk is a resident of The Oaks, a managed alcohol program based in Ottawa. As the name indicates, managed alcohol programs, or MAPs, are treatment facilities that provide homeless alcoholics with housing and small amounts of booze. Every hour, the staff provides the residents with a glass of wine, the volume of which is tailored to their individual needs. The clients don’t get drunk, or anything close to it—they simply retain a manageable buzz, enough to stave off withdrawals and intense cravings.

The justification for managed alcohol programs is simple: Living a life of quiet, low-intensity, sheltered alcoholism is much better than the lifestyles homeless alcoholics often lead, which are inhumane at best, and lethal at worst. Mouthwash often becomes a beverage of choice, street fights are common, and, in colder weather, exposure poses a serious threat. Beyond being dreadful on an individual level, this is also bad for society at large, because the legal trials of street-borne addicts sap public funds.

This was Kunnuk before The Oaks. And there didn’t seem to be much hope of improvement. When he had access to treatment—which he often didn’t—it came in the form of abstinence-based programs that didn’t work very well for him.

This might have something to do with the fact that abstinence treatments for alcoholism don’t work all that well for anyone. Despite the Hollywood images of glitzy rehab vacations and tight-knit Alcoholics Anonymous communities, a growing body of evidence indicates that traditional addiction treatments might not be very effective. Proving this in an ironclad way is difficult, as the vast majority of alcoholism studies don’t have control groups, because leaving alcoholics untreated is unethical. But a fair amount of data casts an unfortunate picture.

Take, for example, a 1989 study called Project MATCH, which originally set out to custom-tailor different rehabilitation strategies to different patient demographics, but ultimately concluded that every treatment seemingly works about the same on almost everyone. While disappointing on its own, the results look particularly bleak in light of a follow-up study published in BMC Public Health in 2005. The authors dug into the Project MATCH data and singled out participants who didn’t attend therapy, or dropped out at some point, but did answer follow-up calls about how they were doing. Their findings were discouraging: The group of patients who dropped out and received zero treatment did almost as well as those who completed the MATCH programs. The paper suggests that only 3 percent of the improvement of treated patients could be attributed to the treatment itself.

The researchers conclude: “The results suggest that current psychosocial treatments for alcoholism are not particularly effective.” They did find that patients who attended more therapy drank less—but they were also the patients who drank less in the first place. In other words, they were looking at a patient selection bias. People who were really devoted to quitting through abstinence treatment were more likely to quit drinking even without it.

MAPs skip the abstinence part in favor of a more pragmatic strategy. This approach isn’t based on entirely new notions. It’s quite similar to safe injection sites, where intravenous drug addicts receive medical supervision and clean needles. MAPs fit squarely into a philosophy of addiction treatment known as harm reduction, adhering to the idea that abstinence needn’t be a necessary ingredient of intervention.

The counterintuitive idea of giving alcoholics access to alcohol as a means of treating their addiction obviously requires a strong argument that it actually works. Data, at this point, is limited, and the sample sizes are small, but initial signs are promising. A 2006 study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal demonstrated that 17 residents of an MAP in Ottawa experienced a significant drop in their interactions with emergency services and police. Another study, published in Harm Reduction Journal 10 years later, in 2016, found that the 18 clients of an MAP in Ontario experienced positive outcomes, “including fewer hospital admissions, detox episodes, and police contacts leading to custody.” One of the leaders of that study, Bernie Pauly of the University of Victoria, is currently expanding this research by gathering data from eight of Canada’s MAPs.

She’s also demonstrated that MAPs can have significant fiscal benefits in a report for the Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia, which stated that an MAP in Thunder Bay, Ontario, saved, by conservative estimates, $1.20 of taxpayer money for every $1 invested. The researchers came to this conclusion by finding the average price of social services utilized by alcoholics who qualified for MAPs but weren’t enrolled in them, and then comparing that to the price per enrolled client. Pauly says that having this evidence makes the idea of MAPs more appealing to those who aren’t necessarily convinced by the harm-reduction approach in and of itself. “It is probably easier in our individual society and our economically driven society to say, yeah, this is a good thing because it’s cheaper,” she says.

Though the economic benefits Pauly uncovered were impressive, she’s ultimately more enthusiastic about the patient outcomes she’s experienced during her research. “People were telling us, ‘Not only do I have housing, and I’m experiencing less harms related to my drinking, but I actually feel like I have a home, I feel like I can reconnect with my family, I feel like I have some hope for the future,’ and that’s pretty huge,” she says.

Moreover, a strange thing happens to the residents at The Oaks: When provided with a constant level of alcohol, they often start drinking less. Though it’s a little counterintuitive, it makes sense. When you’re binge drinking constantly, withdrawal is a constant threat, but when you’re consuming at a steady, more modest pace, you can make the choice to tone it down without the immediate threat of physical reprisal.

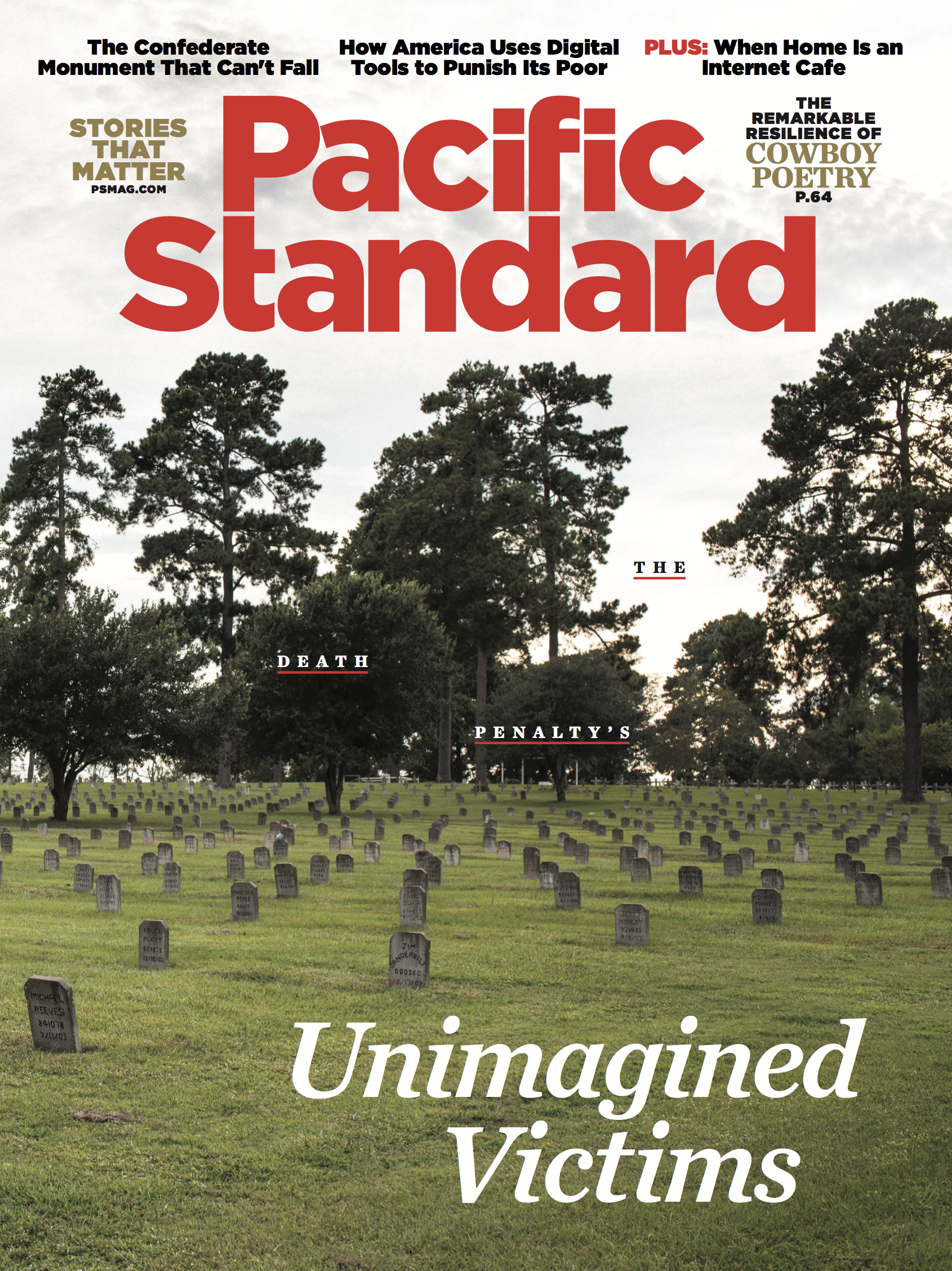

(Photo: Jerome Sessini/Magnum Photos)

Many of the clients I spoke to felt similarly. One longtime client, Corinne Jackson, told me that, prior to the program, she spent her time “barely existing.” She had been dealing with alcoholism for roughly 20 years. “I had tried rehab, I had tried going cold turkey … but always failed miserably.” She felt like abstinence was the only option. “It was kind of like forced upon me, [by] like, family members, and ex-boyfriends,” she says. But it never worked. “There was too many rules, too many chores you had to do. I didn’t get it, and they didn’t get me, and that’s why I left the last in 2009, and I ended up here.”

At the beginning of Jackson’s tenure in the program, it wasn’t a perfect fit—she was, by her own admission, quite belligerent. But she’s progressed considerably, and now she loves the facility, especially the social connection it offers. “We all kind of relate on one level—we’ve all suffered loss, we’ve all suffered great, enormous things, and yet we all get along,” she says. And, at this point, she doesn’t even drink the hourly pour—her consumption has been reduced to a few six-packs of beer a month, which she drinks with the staff’s special permission.

This isn’t necessarily the life she would’ve chosen. But it’s better than a lonely, failing battle against binge drinking. There’s something at stake here, something that The Oaks does, that’s arguably more important than the aversion of liver damage, or the optimization of public funds. It’s dignity: something that these people had lost, but find again here, along with a few glasses of wine.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February 2018 issue of Pacific Standard. Subscribe now and get eight issues/year or purchase a single copy of the magazine.