In a sit-down with CBS’s 60 Minutes earlier this month, President Donald Trump’s erstwhile ideological muse, Steve Bannon, offered a full-throated defense of the “economic nationalism” that’s defined Trump’s two-year hegemony over American political life. Bannon, rebuking the accusations of racism and nativism that have dogged both him and Trump for months, asserted that the campaign rallying cry of “Make America Great Again” was animated by the economic dislocation wrought by open borders and globalization. In Bannon’s telling, the crackdown on undocumented immigrants, the rejection of multinational pacts like the North American Free Trade Agreement and the Paris agreement, and other isolationist impulses are a function of economic, not social, logic.

“They can call me an anti-Semite. They can call me racist. They call me nativist. … As long as we’re driving this agenda for the working men and women of this country, I’m happy,” said the former White House senior strategist. “And, by the way, that’s every nationality … every race, every religion, every sexual preference. As long as you’re a citizen of our country. As long as you’re an American citizen, you’re part of this populist, economic nationalist movement.”

Despite the complicated rhetorical relationship between protectionism and xenophobia—and the alarming rise of more overtly ethno-nationalist elements in the run-up to the 2016 election—”economic nationalism” remains smart branding for the political moment that helped catapult Trump to the presidency. The notion of economic anxiety as the engine of populist movements was given new life when the insurgent campaigns of Trump and Senator Bernie Sanders (D-Vermont) defied all pre-election conventional wisdom. But the latest batch of economic data from the United States Census Bureau suggests that, rather than the downward spiral of the Great Recession, those middle-class voters who helped hand Trump his electoral upset are faring far better than in recent years.

The xenophobia and prejudice exhibited by some Trump voters isn’t a byproduct of economic anxiety—it stems from plain old bigotry.

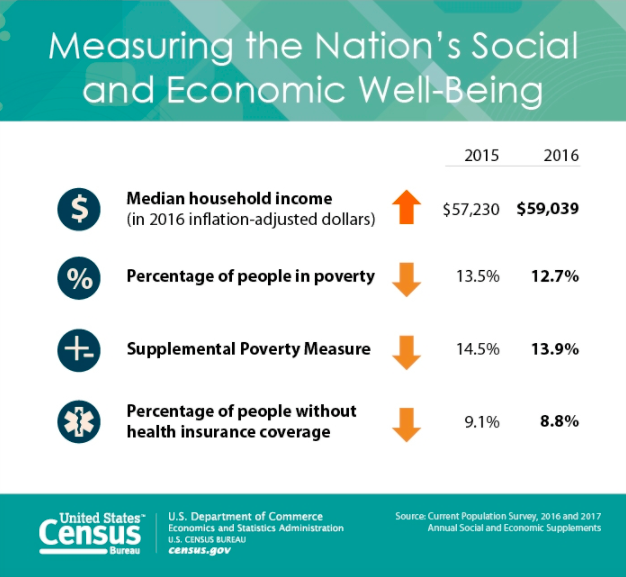

According to a Census Bureau report released on September 12th, the income of middle-class Americans increased in 2016 to the highest level ever recorded by the agency, with median household incomes rising 3.2 percent over 2015 levels, the second straight year of income growth since the start of the global financial crisis in 2007. Although some progressive groups peg real median household income lower than the government estimate due to a methodological change in 2013—1.6 percent less than it was in 2007, and 2.3 percent less than it was in 2000, Dwyer Gunn notes—the number of Americans living in poverty dropped by 2.5 million to a poverty rate of 12.7, “not statistically different” from pre-Recession levels. Even the rate of taxpayers without health insurance hit its lowest level amid the Obamacare frenzy of the 2016 campaign. For middle-class Americans, the U.S. isn’t only “great again” when compared to the eight years under President Barack Obama—it’s, quite literally, already great.

Yes, Trump certainly captured the hearts of the white, blue-collar American workers who felt left behind by the decline of manufacturing—the same people who now find themselves at the mercy of a president who has turned out to in fact be deeply un-populist—but it was the well-educated, well-off middle-class whites who defected from Democratic circles to give him the electoral edge in November. Even college education, the preferred economic stand-in for intelligence, doesn’t clearly capture the class allegiance of Trump swing voters: As the Washington Post noted in June, 20 percent of those “uneducated” working-class Trump voters without a degree boasted more than $100,000 in annual household income. Indeed, a May report from The Atlantic and the Public Religion Research Institute, found that “being in fair or poor financial shape actually predicted support for Hillary Clinton among white working-class Americans, rather than support for Donald Trump,” regardless of education levels.

As such, the economic logic of Trump’s base doesn’t appear to be economic at all. Higher education is usually directly correlated with less unemployment and higher income, but it’s also directly correlated with consistently higher levels of liberal approaches to social and political issues, according to 2016 research from the Pew Research Center—a relationship that makes education a vehicle for attitudes that are “more cosmopolitan, more comfortable with social diversity, more tolerant of social difference,” as Colby College professor Neil Gross told Inside Higher Ed in 2016. This education gap may not be the best measure of the “working-class” voter, but it may indicate a worldview colored by mechanical solidarity, and community through race, family, and creed, rather than a purely economic actor.

All of this data captures an important nuance in understanding the Trump supporter: Despite scaremongering about the death of the American white-working class, the gender and racial gaps in Trump turnout aren’t about white Americans finding themselves suddenly destitute—it’s that other groups suddenly aren’t.

(Photo: Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images)

Indeed, the Census Bureau report indicates that, while white households saw a 2 percent median income increase from 2015 to 2016, black and Hispanic households saw double the gains at 5.7 percent and 4.3 percent respectively; similarly, the poverty rate stayed almost exactly the same for non-Hispanic whites since the Great Recession while falling for virtually everyone else. Trump’s appeal isn’t about absolute loss, but rather a relative loss in sociopolitical power compared to other insurgent demographic groups. At 8.8 percent, the white unemployment rate is still far below the 22 percent rate for black Americans, and the majority of the gains from the economic recovery have flowed to white Americans, with Census data indicating that African Americans are the only racial group in the U.S. still making less than it did in 2000. Even so, white Americans still rend their garments and shriek when faced with literally any sign that their centuries-long cultural hegemony may soon come to an end.

The xenophobia and prejudice exhibited by some Trump voters isn’t a byproduct of economic anxiety—it stems from plain old bigotry. The May 2017 PRRI/The Atlantic report indicated as much, emphasizing fears of “cultural displacement” as the central influence among Trump supporters on issues from immigration to the economy. And consider the exploding trends of self-harm (not just suicide, but chronic illness and drug and alcohol abuse) and despair among white men and women that underlie America’s alarming suicide rate: Their economic hopelessness—”triggered by progressively worsening labor market opportunities at the time of entry for whites with low levels of education,” as Nobel economics laureate Angus Deaton and renowned economics professor Anne Case wrote in March—is not the product of actual disenfranchisement, but rather a sense, accurate or not, that the resources and opportunities once available to “hard-working Americans” are not being stolen away by nefarious political forces rather than the tide of global history.

Just days after his 60 Minutes interview, Bannon fully revealed the shallowness of his economic nationalism when he assailed Trump for aligning himself with Democrats on the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy. Immigration, it seems, is a red line for Trump supporters—just as it was for Bannon a week after Election Day, when he reminded Trump with regard to H1-B visas that “a country is more than an economy … we’re a civic society.” Economic nationalism has always been a shallow proposition for Bannon—and if the latest Census Bureau data is any indication, the same goes for those middle-class white Trump supporters who screwed themselves for a brief taste of revenge.